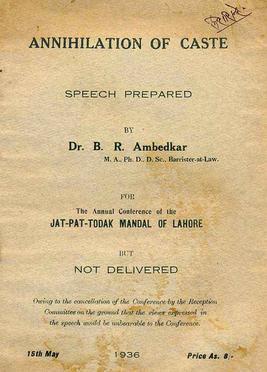

Annhilation of Caste

A timeless critique on the realities of caste in India. Caste is a 2000+ year old layered and hirearchical social seperation and discrimination of people. This undelivered speech by Dr B.R Ambedkar, highlights why caste is a social and politically irreprasable monster and why we need to eradicate it. Originally a speech prepared for an audience of caste Hindus who ultimately rejected it, the work evolved into a manifesto that challenged not only the oppressive structure of the caste system but also the foundations of Hinduism that sustain it. This speech was expected to be delivered in the year 1928, when the Indian freedom struggle was at its peak.

PreReads & Definations :

- Caste Hindu : A person who follows or acknowledge or stays in the fold of the caste system.

- Hindu / Hinduism : There was and still exists no religion called Hinduism. It was first coined by the mughals around the 12-13th century merely as a geographical seperation. The term first used was “al-hind”, meaning “land beyond the Indus”. It is only in the 18th centuary that western ethnography coins the term “Hinduism”. None of the religions texts before the 13-14 centuary has ever mentioned the so called land of hindus as a homogenous group of same religion people. Thus the real defination of the non-existent religion Hinduism is just merely all the different non-agreeing castes put together under a single common naming. More reading here : WikiPedia

- Antyaja/Dalits - An personal belonging to the lower most caste or an untouchable.

- INC - Indian National Congress

You can read the speech here : annihilation of caste

The Problem of Caste

Understanding the Nature of Caste

In his Dasbodh, a socio-politico-religious treatise in Marathi verse, Ramdas asks, addressing the Hindus, can we accept an Antyaja to be our Guru because he is a Pandit (i.e. learned)? He gives an answer in the negative.

The way the caste system has worked has always been that the brahmins or the upper most caste are always the tutors and everyone should listen to what they have to say. And the Dalits and women are not to be educated and it is considered a crime to have them educated.

Is caste a political reform ?

But soon the two wings developed into two parties, a ‘political reform party’ and a ‘social reform party’, between whom there raged a fierce controversy. The ‘political reform party’ supported the National Congress, and the ‘social reform party’ supported the Social Conference. The two bodies thus became two hostile camps. The point at issue was whether social reform should precede political reform. For a decade the forces were evenly balanced, and the battle was fought without victory to either side.

[4:] It was, however, evident that the fortunes of the Social Conference were ebbing fast. The gentlemen who presided over the sessions of the Social Conference lamented that the majority of the educated Hindus were for political advancement and indifferent to social reform; and that while the number of those who attended the Congress was very large, and the number who did not attend but who sympathized with it was even larger, the number of those who attended the Social Conference was very much smaller.

The INC was the only political party that was leading the freedom struggle nation wide at the time of this speech meant to be delivered. While initially the INC was talking social issues like gender etc on the same stage, eventually the fight only became about getting political freedom and not removing the social inequality that existed in the society

Mr. Bonnerji said: “I for one have no patience with those who say we shall not be fit for political reform until we reform our social system. I fail to see any connection between the two. . .Are we not fit (for political reform) because our widows remain unmarried and our girls are given in marriage earlier than in other countries? because our wives and daughters do not drive about with us visiting our friends? because we do not send our daughters to Oxford and Cambridge?” (Cheers [from the audience])

It is important to note here that gender that ambedkar is talking about here is not just that of the Dalits, but also of the upper caste. But the larger question that ambedkar is asking is if social reform has absolutely no bearing on political reform. He further in the book goes in detail to explain and help us understand the same.

Under the rule of the Peshwas in the Maratha country, the untouchable was not allowed to use the public streets if a Hindu was coming along, lest he should pollute the Hindu by his shadow. The untouchable was required to have a black thread either on his wrist or around his neck, as a sign or a mark to prevent the Hindus from getting themselves polluted by his touch by mistake. In Poona, the capital of the Peshwa, the untouchable was required to carry, strung from his waist, a broom to sweep away from behind himself the dust he trod on, lest a Hindu walking on the same dust should be polluted. In Poona, the untouchable was required to carry an earthen pot hung around his neck wherever he went—for holding his spit, lest his spit falling on the earth should pollute a Hindu who might unknowingly happen to tread on it.

Balais was a untouchable community in Central India, and the hindus framed the following rules that they are to follow if they wished to live in their own villages

- Balais must not wear gold-lace-bordered pugrees.

- They must not wear dhotis with coloured or fancy borders.

- They must convey intimation [=information] of the death of any Hindu to relatives of the deceased—no matter how far away these relatives may be living.

- In all Hindu marriages, Balais must play music before the processions and during the marriage.

- Balai women must not wear gold or silver ornaments; they must not wear fancy gowns or jackets.

- Balai women must attend all cases of confinement [= childbirth] of Hindu women.

- Balais must render services without demanding remuneration, and must accept whatever a Hindu is pleased to give.

- If the Balais do not agree to abide by these terms, they must clear out of the villages.

When the Balais protested, they were denied water from the wells, grazing in the lands, walking through the land of the uppercaste, could not access their own feilds. The courts also did nothing about and the whole community had to give up their whole land and move to different places with their family. The question is were they treated any differently in their new homes ? the answer is No.

A most recent event is reported from the village of Chakwara in Jaipur State. It seems from the reports that have appeared in the newspapers that an untouchable of Chakwara who had returned from a pilgrimage had arranged to give a dinner to his fellow untouchables of the village, as an act of religious piety. The host desired to treat the guests to a sumptuous meal, and the items served included ghee (butter) also. But while the assembly of untouchables was engaged in partaking of the food, the Hindus in their hundreds, armed with lathis, rushed to the scene, despoiled the food, and belaboured the untouchables—who left the food they had been served with and ran away for their lives. And why was this murderous assault committed on defenceless untouchables? The reason given is that the untouchable host was impudent enough to serve ghee, and his untouchable guests were foolish enough to taste it. Ghee is undoubtedly a luxury for the rich. But no one would think that consumption of ghee was a mark of high social status. The Hindus of Chakwara thought otherwise, and in righteous indignation avenged themselves for the wrong done to them by the untouchables, who insulted them by treating ghee as an item of their food—which they ought to have known could not be theirs, consistently with the dignity of the Hindus. This means that an untouchable must not use ghee, even if he can afford to buy it, since it is an act of arrogance towards the Hindus. This happened on or about the 1st of April 1936!

Having stated the facts, let me now state the case for social reform. In doing this, I will follow Mr. Bonnerji as nearly as I can, and ask the political-minded Hindus, “Are you fit for political power even though you do not allow a large class of your own countrymen like the untouchables to use public schools? Are you fit for political power even though class of your own countrymen like the untouchables to use public schools? Are you fit for political power even though you do not allow them the use of public wells? Are you fit for political power even though you do not allow them the use of public streets? Are you fit for political power even though you do not allow them to wear what apparel or ornaments they like? Are you fit for political power even though you do not allow them to eat any food they like?” I can ask a string of such questions. But these will suffice.

Every Congressman who repeats the dogma of Mill that one country is not fit to rule another country, must admit that one class is not fit to rule another class. How is it then that the ‘social reform party’ lost the battle?

The Social Conference was a body which mainly concerned itself with the reform of the high-caste Hindu family. It consisted mostly of enlightened high-caste Hindus who did not feel the necessity for agitating for the abolition of Caste, or had not the courage to agitate for it. They felt quite naturally a greater urge to remove such evils as enforced widowhood, child marriages, etc.—evils which prevailed among them and which were personally felt by them. They did not stand up for the reform of the Hindu Society. The battle that was fought centered round the question of the reform of the family. It did not relate to social reform in the sense of the break-up of the Caste System. It [=the break-up of the Caste System] was never put in issue by the reformers. That is the reason why the Social Reform Party lost.

That political reform cannot with impunity take precedence over social reform in the sense of the reconstruction of society, is a thesis which I am sure cannot be controverted.

That the makers of political constitutions must take account of social forces is a fact which is recognized by no less a person than Ferdinand Lassalle, the friend and co-worker of Karl Marx. In addressing a Prussian audience in 1862, Lassalle said: ** The constitutional questions are in the first instance not questions of right but questions of might. The actual constitution of a country has its existence only in the actual condition of force which exists in the country: hence political constitutions have value and permanence only when they accurately express those conditions of forces which exist in practice within a society. **

What is the significance of the Communal Award, with its allocation of political power in defined proportions to diverse classes and communities? In my view, its significance lies in this: that political constitution must take note of social organisation. It shows that the politicians who denied that the social problem in India had any bearing on the political problem were forced to reckon with the social problem in devising the Constitution. The Communal Award is, so to say, the nemesis following upon the indifference to and neglect of social reform. It is a victory for the Social Reform Party which shows that, though defeated, they were in the right in insisting upon the importance of social reform. Many, I know, will not accept this finding.

Let us turn to Ireland. What does the history of Irish Home Rule show? It is well-known that in the course of the negotiations between the representatives of Ulster and Southern Ireland, Mr. Redmond, the representative of Southern Ireland, in order to bring Ulster into a Home Rule Constitution common to the whole of Ireland, said to the Ireland, in order to bring Ulster into a Home Rule Constitution common to the whole of Ireland, said to the representatives of Ulster: “Ask any political safeguards you like and you shall have them.” What was the reply that Ulstermen gave? Their reply was, “Damn your safeguards, we don’t want to be ruled by you on any terms.” People who blame the minorities in India ought to consider what would have happened to the political aspirations of the majority, if the minorities had taken the attitude which Ulster took.

The main question is, why did Ulster take this attitude? The only answer I can give is that there was a social problem between Ulster and Southern Ireland: the problem between Catholics and Protestants, which is essentially a problem of Caste. That Home Rule in Ireland would be Rome Rule was the way in which the Ulstermen had framed their answer. But that is only another way of stating that it was the social problem of Caste between the Catholics and Protestants which prevented the solution of the political problem. This evidence again is sure to be challenged. It will be urged that here too the hand of the Imperialist was at work.

Anyone who has studied the History of Rome will know that the Republican Constitution of Rome bore marks having strong resemblance to the Communal Award. When the kingship in Rome was abolished, the kingly power (or the Imperium) was divided between the Consuls and the Pontifex Maximus. In the Consuls was vested the secular authority of the King, while the latter took over the religious authority of the King. This Republican Constitution had provided that of the two Consuls, one was to be Patrician and the other Plebian. The same Constitution had also provided that of the Priests under the Pontifex Maximus, half were to be Plebians and the other half Patricians. Why is it that the Republican Constitution of Rome had these provisions—which, as I said, resemble so strongly the provisions of the Communal Award? The only answer one can get is that the Constitution of Republican Rome had to take account of the social division between the Patricians and the Plebians, who formed two distinct castes. To sum up, let political reformers turn in any direction they like: they will find that in the making of a constitution, they cannot ignore the problem arising out of the prevailing social order.

The illustrations which I have taken in support of the proposition that social and religious problems have a bearing on political constitutions seem to be too particular. Perhaps they are. But it should not be supposed that the bearing of the one on the other is limited. On the other hand, one can say that generally speaking, History bears out the proposition that political revolutions have always been preceded by social and religious revolutions. The religious Reformation started by Luther was the precursor of the political emancipation of the European people. In England, Puritanism led to the establishment of political liberty. Puritanism founded the new world. It was Puritanism that won the war of American Independence, and Puritanism was a religious movement.

The same is true of the Muslim Empire. Before the Arabs became a political power, they had undergone a thorough religious revolution started by the Prophet Mohammad. Even Indian History supports the same conclusion. The political revolution led by Chandragupta was preceded by the religious and social revolution of Buddha. The political revolution led by Shivaji was preceded by the religious and social reform brought about by the saints of Maharashtra. The political revolution of the Sikhs was preceded by the religious and social revolution led by Guru Nanak. It is unnecessary to add more illustrations. These will suffice to show that the emancipation of the mind and the soul is a necessary preliminary for the political expansion of the people.

It is only fair to say that, every political reform has to be preceeded by social reform, else, the political reform altough may win, is meaningless and has no difference before and after the victory.

Why social reform is necessary for economic reform

Let me now turn to the Socialists. Can the Socialists ignore the problem arising out of the social order? The Socialists of India, following their fellows in Europe, are seeking to apply the economic interpretation of history to the facts of India. They propound that man is an economic creature, that his activities and aspirations are bound by economic facts, that property is the only source of power. They therefore preach that political and social reforms are but gigantic illusions, and that economic reform by equalization of property must have precedence over every other kind of reform.

Altough, the socialists have changed their stance around the 1970 - 80’s agreeing that caste was indeed the root cause and is a directly linked between political and economic of the society, the statement made here by Ambedkar is i 1928.

Why do millionaires in India obey penniless Sadhus and Fakirs? Why do millions of paupers in India sell their trifling trinkets which constitute their only wealth, and go to Benares and Mecca? That religion is the source of power is illustrated by the history of India, where the priest holds a sway over the common man often greater than that of the magistrate, and where everything, even such things as strikes and elections, so easily takes a religious turn and can so easily be given a religious twist.

Take the case of the Plebians of Rome, as a further illustration of the power of religion over man. It throws great light on this point. The Plebians had fought for a share in the supreme executive under the Roman Republic, and had secured the appointment of a Plebian Consul elected by a separate electorate constituted by the Commitia Centuriata, which was an assembly of Plebians. They wanted a Consul of their own because they felt that the Patrician Consuls used to discriminate against the Plebians in carrying on the administration. They had apparently obtained a great gain, because under the Republican Constitution of Rome one Consul had the power of vetoing an act of the other Consul.

But did they in fact gain anything? The answer to this question must be in the negative. The Plebians never could get a Plebian Consul who could be said to be a strong man, and who could act independently of the Patrician Consul. In the ordinary course of things the Plebians should have got a strong Plebian Consul, in view of the fact that his election was to be by a separate electorate of Plebians. The question is, why did they fail in getting a strong Plebian to officiate as their Consul?

The answer to this question reveals the dominion which religion exercises over the minds of men. It was an accepted creed of the whole Roman populus [=people] that no official could enter upon the duties of his office unless the Oracle of Delphi declared that he was acceptable to the Goddess. The priests who were in charge of the temple of the Goddess of Delphi were all Patricians. Whenever therefore the Plebians elected a Consul who was known to be a strong party man and opposed to the Patricians—or “communal,” to use the term that is current in India—the Oracle invariably declared that he was not acceptable to the Goddess. This is how the Plebians were cheated out of their rights.

But what is worthy of note is that the Plebians permitted themselves to be thus cheated because they too, like the Patricians, held firmly the belief that the approval of the Goddess was a condition precedent to the taking charge by an official of his duties, and that election by the people was not enough. If the Plebians had contended that election was enough and that the approval by the Goddess was not necessary, they would have derived the fullest benefit from the political right which they had obtained. But they did not. They agreed to elect another, less suitable to themselves but more suitable to the Goddess—which in fact meant more amenable to the Patricians. Rather than give up religion, the Plebians give up the material gain for which they had fought so hard. Does this not show that religion can be a source of power as great as money, if not greater?

The fallacy of the Socialists lies in supposing that because in the present stage of European Society property as a source of power is predominant, that the same is true of India, or that the same was true of Europe in the past. Religion, social status, and property are all sources of power and authority, which one man has, to control the liberty of another. One is predominant at one stage; the other is predominant at another stage. That is the only difference. If liberty is the ideal, if liberty means the destruction of the dominion which one man holds over another, then obviously it cannot be insisted upon that economic reform must be the one kind of reform worthy of pursuit. If the source of power and dominion is, at any given time or in any given society, social and religious, then social reform and religious reform must be accepted as the necessary sort of reform.

However, what I would like to ask the Socialists is this: Can you have economic reform without first bringing about a reform of the social order? The Socialists of India do not seem to have considered this question. I do not wish to do them an injustice. I give below a Socialists of India do not seem to have considered this question. I do not wish to do them an injustice. I give below a quotation from a letter which a prominent Socialist wrote a few days ago to a friend of mine, in which he said, “I do not believe that we can build up a free society in India so long as there is a trace of this ill-treatment and suppression of one class by another. Believing as I do in a socialist ideal, inevitably I believe in perfect equality in the treatment of various classes and groups. I think that Socialism offers the only true remedy for this as well as other problems.”

Now the question that I would like to ask is: Is it enough for a Socialist to say, “I believe in perfect equality in the treatment of the various classes?” To say that such a belief is enough is to disclose a complete lack of understanding of what is involved in Socialism. If Socialism is a practical programme and is not merely an ideal, distant and far off, the question for a Socialist is not whether he believes in equality. The question for him is whether he minds one class ill- treating and suppressing another class as a matter of system, as a matter of principle—and thus allowing tyranny and oppression to continue to divide one class from another.

Now it is obvious that the economic reform contemplated by the Socialists cannot come about unless there is a revolution resulting in the seizure of power. That seizure of power must be by a proletariat.

While the above idea is true in a European context, in the context of caste and socialism, Ambedkar asks the below questions.

The first question I ask is: Will the proletariat of India combine to bring about this revolution? What will move men to such an action? It seems to me that, other things being equal, the only thing that will move one man to take such an action is the feeling that other men with whom he is acting are actuated by a feeling of equality and fraternity and—above all—of justice. Men will not join in a revolution for the equalization of property unless they know that after the revolution is achieved they will be treated equally, and that there will be no discrimination of caste and creed.

The assurance of a Socialist leading the revolution that he does not believe in Caste, I am sure will not suffice. The assurance must be the assurance proceeding from a much deeper foundation—namely, the mental attitude of the compatriots towards one another in their spirit of personal equality and fraternity. Can it be said that the proletariat of India, poor as it is, recognises no distinctions except that of the rich and the poor? Can it be said that the poor in India recognize no such distinctions of caste or creed, high or low? If the fact is that they do, what unity of front can be expected from such a proletariat in its action against the rich? How can there be a revolution if the proletariat cannot present a united front?

Suppose for the sake of argument that by some freak of fortune a revolution does take place and the Socialists come into power; will they not have to deal with the problems created by the particular social order prevalent in India? I can’t see how a Socialist State in India can function for a second without having to grapple with the problems created by the prejudices which make Indian people observe the distinctions of high and low, clean and unclean. If Socialists are not to be content with the mouthing of fine phrases, if the Socialists wish to make Socialism a definite reality, then they must recognize that the problem of social reform is fundamental, and that for them there is no escape from it.

Ambedkar highlights that if the socialists fail to take social reform before the revolution, then they will have to deal with it after the revolution. He concludes saying, it is impossible to have political or economic revolution, without a social revolution.

He will be compelled to take account of Caste after the revolution, if he does not take account of it before the revolution. This is only another way of saying that, turn in any direction you like, Caste is the monster that crosses your path. You cannot have political reform, you cannot have economic reform, unless you kill this monster.

Is caste just a division of labour or division of labourers ?

Now the first thing that is to be urged against this view is that the Caste System is not merely a division of labour. **It is also a division of labourers. **

Civilized society undoubtedly needs division of labour. But in no civilized society is division of labour accompanied by this unnatural undoubtedly needs division of labour. **But in no civilized society is division of labour accompanied by this unnatural division of labourers into watertight compartments **

The Caste System is not merely a division of labourers which is quite different from division of labour—it is a hierarchy in which the divisions of labourers are graded one above the other. In no other country is the division of labour accompanied by this gradation of labourers.

A good way to understand this even in today’s context is researching on some questions like “The top 10 rich people of this country belong to what caste ?” or “What caste does my manager belong to and what percentage of managers actually belong to lower castes ?” “How many of my collegues are actually Dalits ?” “How many students studying abroad are actually Dalits ?”

#TODO: Add sources to read here

here is also a third point of criticism against this view of the Caste System. This division of labour is not spontaneous, it is not based on natural aptitudes. Social and individual efficiency requires us to develop the capacity of an individual to the point of competency to choose and to make his own career. This principle is violated in the Caste System, in so far as it involves an attempt to appoint tasks to individuals in advance—selected not on the basis of trained original capacities, but on that of the social status of the parents.

Industry is never static. It undergoes rapid and abrupt changes. With such changes, an individual must be free to change his occupation. Without such freedom to adjust himself to changing circumstances, it would be impossible for him to gain his livelihood. Now the Caste System will not allow Hindus to take to occupations where they are wanted, if they do not belong to them by heredity. If a Hindu is seen to starve rather than take to new occupations not assigned to his Caste, the reason is to be found in the Caste System. By not permitting readjustment of occupations, Caste becomes a direct cause of much of the unemployment we see in the country.

This remains absolutely true even today. #TODO: Add sources to read here

The division of labour brought about by the Caste System is not a division based on choice. Individual sentiment, individual preference, has no place in it. It is based on the dogma of predestination.

#TODO: Add the news link that talks about arundathiyars and also to kakoos documentary and pariyerum perumal and mamannan movie

What efficiency can there be in a system under which neither men’s hearts nor their minds are in their work? As an economic organization Caste is therefore a harmful institution, inasmuch as it involves the subordination of man’s natural powers and inclinations to the exigencies of social rules.

Caste as a question of racial purity

For long humans have always had the idea of racial purity among men for ex : Whites not allowed to marry the black etc.

It is said that the object of Caste was to preserve purity of race and purity of blood.

Now ethnologists are of the opinion that men of pure race exist nowhere and that there has been a mixture of all races in all parts of the world.

Mr. D. R. Bhandarkar in his paper on “Foreign Elements in the Hindu Population”

Mr. D. R. Bhandarkar in his paper on “Foreign Elements in the Hindu Population” has stated that “There is hardly a class or Caste in India which has not a foreign strain in it. There is an admixture of alien blood not only among the warrior classes —the Rajputs and the Marathas—but also among the Brahmins who are under the happy delusion that they are free from all foreign elements”

The Caste system cannot be said to have grown as a means of preventing the admixture of races, or as a means of maintaining purity of blood.

As a matter of fact [the] Caste system came into being long after the different races of India had commingled in blood and culture. To hold that distinctions of castes are really distinctions of race, and to treat different castes as though they were so many different races, is a gross perversion of facts. What racial affinity is there between the Brahmin of the Punjab and the Brahmin of Madras? What racial affinity is there between the untouchable of Bengal and the untouchable of Madras? What racial difference is there between the Brahmin of the Punjab and the Chamar of the Punjab? What racial difference is there between the Brahmin of Madras and the Pariah of Madras? The Brahmin of the Punjab is racially of the same stock as the Chamar of the Punjab, and the Brahmin of Madras is of the same race as the Punjab is racially of the same stock as the Chamar of the Punjab, and the Brahmin of Madras is of the same race as the Pariah of Madras.

[The] Caste system does not demarcate racial division. [The] Caste system is a social division of people of the same race.

Assuming it, however, to be a case of racial divisions, one may ask: What harm could there be if a mixture of races and of blood was permitted to take place in India by intermarriages between different castes? Men are no doubt divided from animals by so deep a distinction that science recognizes men and animals as two distinct species. But even scientists who believe in purity of races do not assert that the different races constitute different species of men. They are only varieties of one and the same species. As such they can interbreed and produce an offspring which is capable of breeding and which is not sterile.

An immense lot of nonsense is talked about heredity and eugenics in defence of the Caste System.

The basic principle of eugenics, because few can object to the improvement of the race by judicious mating.

But one fails to understand how the Caste System secures judicious mating. [The] Caste System is a negative thing. It merely prohibits persons belonging to different castes from intermarrying. It is not a positive method of selecting which two among a given caste should marry.

f Caste is eugenic in origin, then the origin of sub-castes must also be eugenic. But can anyone seriously maintain that the origin of sub-castes is eugenic? I think it would be absurd to contend for such a proposition, and for a very obvious reason. If caste means race, then differences of sub-castes cannot mean differences of race, because sub-castes become ex hypothesia[= by hypothesis] sub-divisions of one and the same race. Consequently the bar against intermarrying and interdining between sub-castes cannot be for the purpose of maintaining purity of race or of blood. If sub-castes cannot be eugenic in origin, there cannot be any substance in the contention that Caste is eugenic in origin.

Again, if Caste is eugenic in origin one can understand the bar against intermarriage. But what is the purpose of the interdict placed on interdining between castes and sub-castes alike? Interdining cannot infect blood, and therefore cannot be the cause either of the improvement or of [the] deterioration of the race.

Caste absolutely has no scientific origins.

Even today, eugenics cannot become a practical possibility unless we have definite knowledge regarding the laws of heredity. Prof. Bateson in his Mendel’s Principles of Heredity says, “There is nothing in the descent of the higher mental qualities to suggest that they follow any single system of transmission. It is likely that both they and the more marked developments of physical powers result rather from the coincidence of numerous factors than from the possession of any one genetic element.” To argue that the Caste System was eugenic in its conception is to attribute to the forefathers of present-day Hindus a knowledge of heredity which even the modern scientists do not possess.

Can caste unite to form a nation ?

Caste does not result in economic efficiency. Caste cannot improve, and has not improved, the race. Caste has however done one thing. It has completely disorganized and demoralized the Hindus.

The first and foremost thing that must be recognized is that Hindu Society is a myth. The name Hindu is itself a foreign name. It was given by the Mohammedans to the natives for the purpose of distinguishing themselves [from foreign name. It was given by the Mohammedans to the natives for the purpose of distinguishing themselves [from them]. It does not occur in any Sanskrit work prior to the Mohammedan invasion. They did not feel the necessity of a common name, because they had no conception of their having constituted a community.

Hindu Society as such does not exist. It is only a collection of castes. Each caste is conscious of its existence. Its survival is the be-all and end-all of its existence. Castes do not even form a federation. A caste has no feeling that it is affiliated to other castes, except when there is a Hindu-Muslim riot. On all other occasions each caste endeavours to segregate itself and to distinguish itself from other castes.

Each caste not only dines among itself and marries among itself, but each caste prescribes its own distinctive dress. What other explanation can there be of the innumerable styles of dress worn by the men and women of India, which so amuse the tourists?

Indeed the ideal Hindu must be like a rat living in his own hole, refusing to have any contact with others. There is an utter lack among the Hindus of what the sociologists call “consciousness of kind.” There is no Hindu consciousness of kind. In every Hindu the consciousness that exists is the consciousness of his caste. That is the reason why the Hindus cannot be said to form a society or a nation

There are, however, many Indians whose patriotism does not permit them to admit that Indians are not a nation, that they are only an amorphous mass of people. They have insisted that underlying the apparent diversity there is a fundamental unity which marks the life of the Hindus, inasmuch as there is a similarity of those habits and customs, beliefs and thoughts, which obtain all over the continent of India. Similarity in habits and customs, beliefs and thoughts, there is. But one cannot accept the conclusion that therefore, the Hindus constitute a society.

What constitutes a society ?

Men do not become a society by living in physical proximity, any more than a man ceases to be a member of his society by living so many miles away from other men.

econdly, similarity in habits and customs, beliefs and thoughts, is not enough to constitute men into society. Things may be passed physically from one to another like bricks. In the same way habits and customs, beliefs and thoughts of one group may be taken over by another group, and there may thus appear a similarity between the two. Culture spreads by diffusion, and that is why one finds similarity between various primitive tribes in the matter of their habits and customs, beliefs and thoughts, although they do not live in proximity. But no one could say that because there was this similarity, the primitive tribes constituted one society. This is because similarity in certain things is not enough to constitute a society

Men constitute a society because they have things which they possess in common. To have similar things is totally different from possessing things in common. And the only way by which men can come to possess things in common with one another is by being in communication with one another. This is merely another way of saying that Society continues to exist by communication—indeed, in communication. To make it concrete, it is not enough if men act in a way which agrees with the acts of others. Parallel activity, even if similar, is not sufficient to bind men into a society.

This is proved by the fact that the festivals observed by the different castes amongst the Hindus are the same. Yet these parallel performances of similar festivals by the different castes have not bound them into one integral whole.

For that purpose what is necessary is for a man to share and participate in a common activity, so that the same emotions are aroused in him that animate the others. Making the individual a sharer or partner in the associated activity, so that he feels its success as his success, its failure as his failure, is the real thing that binds men and makes a society of them. The Caste System prevents common activity; and by preventing common activity, it has prevented the Hindus from becoming a society with a unified life and a consciousness of its own being.

Altough, this is a fair conclusion, Ambedkar further in the book argues, that caste hindus do share the common feelings, success and failures but these are that of the society but that of the caste.

Caste is Antisocial by design

he Hindus often complain of the isolation and exclusiveness of a gang or a clique and blame them for anti-social spirit. But they conveniently forget that this anti-social spirit is the worst feature of their own Caste System. One caste enjoys singing a hymn of hate against another caste as much as the Germans enjoyed singing their hymn of hate against the English during the last war [=World War I].

The literature of the Hindus is full of caste genealogies in which an attempt is made to give a noble origin to one caste and an ignoble origin to other castes. The Sahyadrikhand is a notorious instance of this class of literature.

This anti-social spirit is not confined to caste alone. It has gone deeper and has poisoned the mutual relations of the sub-castes as well. In my province the Golak Brahmins, Deorukha Brahmins, Karada Brahmins, Palshe Brahmins, and Chitpavan Brahmins all claim to be sub-divisions of the Brahmin caste. But the anti-social spirit that prevails between them is quite as marked and quite as virulent as the anti-social spirit that prevails between them and other non-Brahmin castes. There is nothing strange in this.

An anti-social spirit is found wherever one group has “interests of its own” which shut it out from full interaction with other groups, so that its prevailing purpose is protection of what it has got.

The Brahmin’s primary concern is to protect “his interest” against those of the non-Brahmins; and the non-Brahmins’ primary concern is to protect their interests against those of the Brahmins. The Hindus, therefore, are not merely an assortment of castes, but are so many warring groups, each living for itself and for its selfish ideal.

It is also interesting at this point that Ambedkar in all writings has tried to predeminantly address men over women or atleast the writings indicate that structure.

There is another feature of caste which is deplorable. The ancestors of the present-day English fought on one side or the other in the Wars of the Roses and the Cromwellian War. But the descendants of those who fought on the one side do not bear any animosity—any grudge—against the descendents of those who fought on the other side. The feud is forgotten. But the present-day non-Brahmins cannot forgive the present-day Brahmins for the insult their ancestors gave to Shivaji. The present-day Kayasthas will not forgive the present-day Brahmins for the infamy cast upon their forefathers by the forefathers of the latter. To what is this difference due? Obviously to the Caste System. The existence of Caste and Caste Consciousness has served to keep the memory of past feuds between castes green, and has prevented solidarity